Recently I prepared a short summary paper for a press release. This has started to spark some interest and debate about these features. Because I feel they need protecting, I have added a great deal of field data to this website and prepared permit requests to the National Park Service to conduct more research. In addition, for those interested I have provided the history of my research.

Tomales Point is about 30 kilometers north of San Francisco in the Point Reyes National Park. You can visit this site anytime by going to the northernmost end of the park and hiking 2 kilometers north on the Pierre Ranch Trail. This is also a Tule Elk preserve so you will probably see some spectacular wildlife along the way.

The MIAMO team was attracted to this area because of the stone lines.

These lines are composed of large flat rocks made of a granitic type stone called Tonolite. They are surrounded by artificial mounds covered by similar stones.

Until recently the lines were ignored. Historians guessed that they were once a wall built by farmers in the 1800s. But in 2013 two high school students Kate Lida and Emily Wearing studied the lines. They could not prove that the line was once a wall, but it is possible it was built by dairy farmers. We do not know how old the line is so it could have been built by first Americans. A report of the work was co-authored by their professor Dr. Michael Wing and published in 2015.

Michael Wing, Kate Lida and Emily Wearing, 2015 Stone-by-Stone Metrics at Point Reyes National Seashore, Marine County, Alta, California, California Archaeology, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 245-264.

Below are a variety of views of the study area and some features.

As you approach the study area from the south you can see some of the artificial megalithic features. From left to right are the platform mounds and the Sol Mound.

Above is a view of the first platform mound from down slope. This area is very complex. Off the photograph to the right is a spring. In the foreground of the photograph is the remains of a stone circle. At the top of the photo is the platform. The platform is composed of compacted soil. The perimeter is protected from erosion by a layer of stones.

A solitary mound south of the main area is the Compass Mound above. The mound is composed of soil and rocks mixed together and about 1 meter tall. It is level on top with one block placed at the center of the mound. The block is shaped by fractures and is aligned north to south.

Above is the Goliath Mound. This boulder is flat on the bottom and rests on five blocks arranged in a circle. The Goliath block is 3 meters tall and 2 meters in diameter. The alcove is seen here as photographed from the stone line directly to the west. The photograph below is the solstice stone directly east of Goliath and where the sun sets on the Winter and Summer solstices. The entire line before coming to this stone is flat like steppingstones. This is the 38th stone counting from the cliff edge and the first upright stone in the line.

HISTORY OF THE RESEARCH

I am a geologist and not an archaeologist. And so, the story of the discovery of the Tomales Point Mounds begins with the rocks. Archaeologists and historians have long ago abandoned any interest in Tomales Point because they believe there are no artifacts to be found there. In fact, one archaeologist commented on one of my papers, “So you think you have discovered something hundreds of years of study have missed”?

Well, there are artifacts on Tomales Point. There is a constructed line of rocks crossing the crest of the peninsula. And when a friend of mine heard that I was interested in such things, she said I should take a look. I have visited the Tomales peninsula many times. There are rocks there to be sure. Natural outcrops of bedrock are rare, but large and small boulders are scattered about the study area near the stone lines. I have found no arrow heads or broken pottery, no ancient villages or shell debris middens. But historians and archaeologists agree that there are lines made of rocks present. And even archaeologists would have to agree that the stone lines are artificial.

Some of the rocks in the lines are very large. Meters in length, these rocks qualify to be called “megaliths”. And the lines qualify as megalithic structures. Surrounding the lines are piles of rock, gravel and dirt. Previous geologists have not commented on these piles. I also found them of little interest at first. But, the more I looked at the lines, the more I needed to look at the piles of rocks. Archaeologists have deemed the megalithic lines to be of little interest in the study of ancient peoples because they assume the lines were built by 19th century farmers. Suggested uses were the beginning of a wall and marking of a property line. Despite no written documentation of the construction of the lines, this is all history has to say. And despite the fact that there is an old map that shows the lines were constructed before 1854 and probably predate farming in the area, the conclusion seems to have stuck.

So, why did a geologist decide to study something that has been abandoned by academics in history and archaeology long ago? The answer actually starts in New Mexico. Years ago. I was browsing books in the library at the University of California in Santa Cruz when I came across a book of maps that reported finding ancient roads crossing the deserts of New Mexico and Arizona.

The curious ancient roads of the Chacoan Anasazi are a fairly recent discovery by southwestern archaeologists. In the 1970s and 80s some of these archaeologists started examining aerial photographs to find new sites that might be excavated. As their examination proceeded, they started finding dark lines on several photographs that were hard to explain. In geology we call these dark lines photographic lineaments. If we inspect the lineaments on the ground, we often find they are abandoned dirt roads or property lines. But sometimes they can only be explained by geologic features like long rock fractures or faults. Living and working in California I have spent a lot of time studying fractures and faults caused by earthquakes and I am very familiar with photographic lineaments.

After conducting ground surveys of some of the lineaments in New Mexico archaeologists identified some as ancient roads. These roads often have distinct features of width and depth and often were located with or near ancient stone structures. Broken pottery is found along the roads as are some short walls and other embellishments. In some cases, the roads cross steep rocky areas and in those locations, archaeologists have found steps carved into the rock. Roads with these added features are called “formalized” by archaeologists.

I became very interested in these photographic lineaments reported in New Mexico and spent some time reading about the work that documents their discovery on photographs and confirmation on the ground by field studies by the National Park Service and Bureau of Land Management. The work by various scientists of these agencies determined that many of the lines were in fact constructed some one thousand years ago by people commonly known as the Anasazi. Anasazi is a scientific term composed of words from the Navajo language and means, “those who came before”. The pueblo Indians of New Mexico and Arizona consider the Anasazi their ancestors. Archaeologists now think that large excavated ancient structures in Chaco Canyon may have been the center point from which many roads emanated. These roads are thought to connect other archaeological sites hundreds of kilometers away from Chaco Canyon. And so, the various ancient buildings and roads are collectively part of the Chacoan Culture. The Chacoan Culture is also known as the Anasazi and Ancestral Puebloans.

I visited some of the archaeologists who conducted the work and then started looking more closely at the features on the ground by hiking across the desert. Much of the land where these lines were found is on the Navajo Nation. The director of the Navajo Nation Historic Preservation Department, Ron Maldonado was kind enough to provide me with permits to explore the region. In addition, one of the original scientists involved in the discovery of the photographic lineaments and roads, John Stein, agreed to help me as a guide to some of the archaeological sites.

My original intention was to approach the problem as a geologist. In that way I thought I might provide data and insights on the ancient road theory. Geologists tend to cover a lot of ground as they map rock exposures to reconstruct the history of the earth. Archaeologists are generally more focused on specific sites or groups of sites and spend enormous amounts of time on the careful excavation of sites. My plan was to cover large areas and provide archaeologists with maps of various ancient sites. In this way, roads might also be found and the regional distribution of archaeological sites and artifacts might help in the reconstruction of the Chacoan Culture.

Two decades and thousands of kilometers walked, I and my team have now found dozens of new sites and several new roads. More importantly we have found that the roads are far longer than first thought and may extend hundreds of kilometers across both New Mexico and Arizona and probably into Colorado and Utah. I published two papers on the roads and continue to compile new mapped data. Some of which I have reproduced in this website.

As it happened my friend and colleague Renee Buchannon had participated in the archaeological survey of Tomales Point and was familiar with the stone lines. When she found out that I was studying the archaeology of the Anasazi in northwestern New Mexico and linear features like the line of rocks at Tomales Point, she suggested that I take look at something closer to home.

Before visiting Tomales Point I tried to find any technical reports about the archaeology. To my surprise there is no formal research reported apparently because as noted above no artifacts of significance have been found. I did find a paper in the California Journal of Archaeology by a professor and two of his students. This is an amazing piece of work conducted as a high school senior project at Sir Francis Drake High School.

In 2013 and 2014 under direction by Dr. Michael Wing, Kate Lida and Emily Wearing conducted a study of the rock lines by researching the history of the area and measuring each rock in the lines. They produced a database of the stone metrics including length, width and height of each stone and other features like gaps and the number of stones adjacent to the line (Wing, Lida, & Wearing, 2014). From these data and available historic documents, they made comparisons to other stone walls in the region. They suggested that the lines may have been made in the 19th century by farmers. But, they also said that their data did not determine the age or who actually constructed the stone lines. While the historic hypothesis is one explanation for the origin and function of the lines, the stone metrics data set reveals several features that do not suggest a wall or property line.

Professor Wing was kind enough to share their data set on the metrics of the stones in the line. And, I found their work quite intriguing. The detailed descriptions are particularly useful for quantitative analysis and Wing and his students conducted some statistical studies to evaluate if the lines were similar to walls constructed in New England and/or what are thought to be Native American walls nearby.

The first thing I noticed about the stone metrics was how variable they were in size. Many of the stones are small and elongate. Partially buried, they are small enough to have been used for a foundation. But, some of the stones are very large and probably weigh thousands of pounds. I could not imagine why a farmer would excavate and install stones of this size to make a simple wall. Wing, Lida and Wearing did not conclude that the lines were in fact former walls. And, they suggested that paleoindians could have constructed them. But, the mystery remains, why were they constructed and when. Only when I started to visit the site did I realize how much bigger the mystery of the stone lines would be.

After collecting addition data on the stone lines and mapping what I called Stone line 1, began looking at the near by stone mounds. The mounds turned out to be very helpful in formulating a hypothesis that the lines and mounds are artificial and constructed by someone other than farmers.

There are at least three mounds that show no evidence of natural formation or as bedrock outcrops. There are several features that suggest the mounds or parts of the mounds were constructed. While I continued to search for natural explanation for these mounds, my search area grew and in the process I discover two distinct artificial features.

The first was a large star petroglyph on the side of a massive boulder perched on a semicircular ring of smaller stones. The second was a buried circular excavation in the bedrock. So, in addition to an extensive and ongoing geologic examination of the lines and stone piles, two features that have archaeological significance have also been found.

It has always been my intention to attract archaeologists to this site with the intention of advising the National Park Service on how to protect them. They presently already are being damaged by the heavy traffic of hikers who follow the trail that passes right across the lines and among the artificial mounds. This trail should be rerouted.

Recently I was contacted by Dr. Lou-Anne Fauteck Makes-Marks who has seen early versions of my paper on the lines and mounds. She found many features indicative of a sacred landscape. Luan and I are now working together to raise awareness about these features.

WHY DO I THINK THE STONE LINES WERE NOT BUILT BY FARMERS. AND, WHY WERE THEY BUILT?

The basic conclusion from historians is the stone lines were once a wall or they mark a property line. There is no wall there now only stones set end-to-end in the soil like steppingstones. Either the wall was never built of the stones of the wall have been taken away. There is no written evidence to support this idea, no journals or notes or newspaper reports or land descriptions. There is an1854 map that shows a fence line that is close to the stone line location. The line is not described, so it could be a stone or wooden fence or an old trail or anything else. Now, I could say, “why would any farmer put so much effort into a property line”, but people have their own reasons for doing things. So, what else do we have to figure out what these lines are about?

WE HAVE THE LINES.

There are two lines. Designated herein as “Stone Line 1” and “Stone Line 2” . Stone Line 1, is a group of 233 stones 160 meters long and follows a compass bearing of north 28 degrees east across Tomales Point. The stones are numbered in this study from south to north with the first stone occurring near the western cliff edge of the peninsula. The end of Stone Line 1 is marked by stone #233 and is located near the crest of the peninsula ridge. Stone Line 2 begins ten meters north of the northeastern end of Stone Line 1. It is composed of 75 stones arrayed over 88 meters and follows a compass bearing of north 35 degrees east. Some historians suggest that the stones are assembled into a single line (DeRooy & Livingstone 2008). This requires the assumption that the two lines present today were once connected by a now absent line of stones approximately ten meters in length. There is no evidence of these “connecting” stones (e.g. partial line, scattered rocks, or geomorphic expression) present at the site. However, maps referenced by Wing et. al. (2015) show the two stones lines as one single line crossing the peninsula. For this study it is inferred that there originally were two stone lines.

The compass bearing of Stone Line 1 can be projected to a local bedrock outcrop five kilometers to the northeast along the ridge crest bordering the northeast shore of Tomales Bay. This bedrock outcrop can be seen from Tomales Point and is formed from sandstone of the Wilson Grove Formation. The outcrop is composed of several hoodoos . The geologic term “hoodoo” refers to a column, pinnacle or pillar of rock produced by differential weathering forming grotesque shapes (Bates & Jackson, 1987). These outcrops are incised in several locations resulting in shallow caves whose openings face to the southwest toward Tomales Point and the stone lines. In some outcrops the caves appear modified to create flat rock bottoms and may have been occupied in the past.

Individual Stones of Stone Line I

A description of the characteristics of the stones provides evidence that the stone lines were constructed with several embellishments. There are 233 stones in Stone Line I. With rare exception these stones lie at the ground surface surrounded by soil much like a series of stepping stones. Most of these stones are flat and in some cases partially covered by vegetation (Figure 5). The stones appear imbedded in the soil and may be sitting on the natural bedrock below, suggesting they are of consistent thickness unless some or all are keyed into the bedrock which cannot be determined without excavation. In some places the stones occur elevated above the ground surface. Most of these elevated stones show signs of displacement due to differential compaction of soils, animal burrows, frost wedging and other ground disturbing processes. There is a small number of stones that are installed in an upright position and stand taller than the adjacent stones. These upright stones are described in more detail below.

Cobbles and boulders around natural outcrops in the study area are typically sub-rounded to rounded by erosion. Many of the stones appear rounded and may have been collected from nearby weathered outcrops. However many of the stones in the lines are angular and appear to have been quarried and or shaped before placement stone #65 is an example of a angular stone placed upright along the line (Figure 6). This is particularly striking for the stones that are shaped like elongate rectangles. These elongate stones are typically 0.5 meters in width, but may be up to 1.5 meters in length. In most cases the long stones are placed with the long axis in alignment with the compass direction of the line. However, several long stones have been identified that are placed with the long axis transverse to the trend of the line. These transverse stones vary in size and do not appear in any order or standard spacing distance along the line. Wing et al (2015) suggest that transverse stone are generally smaller that line parallel stones. However, there is a far greater number of stone shapes and sizes than elongate and transverse. Figure ___ is a graphic representation of the mapped stones in line I. From this figure it can be seen that elongate stones parallel to the line vary in length and width and as Wing et al have suggested some appear quite large. The same can be said for transverse stones (e.g. stones _____). However, there are many stones that are square. Using the Wing et al 2014 stone – by- stone measurement dataset. There are 75 transverse stones, ___ elongate parallel stones and ___ square stones. As noted above the average widthof the stones and the line is 0.5 meters. However, throughout the line there are numerous much wider stones (e.g. stones ).

Gaps between the stones are typically no more than .01 to .02 meters and in several cases the stones lie directly against one another. There are places along the line where larger gaps occur and these gaps are typically associated with “satellite” stones. Satellite stones lie adjacent to the line, but are not part of the line. There is a close correlation between wider gaps and numerous satellite stones nearby, suggesting the satellites were once part of the line and have been displaced. However, there are two gaps with relatively long lengths of 1.0 and 1.3 meters and where satellites were not found. These gaps occur at 39 and 75 meters along the line respectively as measured from the southern end. There are at least two cases where several satellites occur along the line and not adjacent to gaps. In these locations the satellites occur near tall stones and suggest that there may have been some additional structure to the line at these points.

Of the 233 stones most occur at, or less than 10 centimeters above the ground surface. There are 11 stones that stand above the ground surface between 0.4 and 0.9 meters. As noted above, most of these taller stones show signs of displacement due to natural ground disturbing processes. There are however four stones that are clearly placed to stand taller than the rest of the stones making up the line and were deliberately placed in an up-right position. They are designated herein by name and their specifications are provided in Table 1. Among these taller stones the “Tower Stone” is the most prominent and is bounded on either side along the line by very large flat slabs (Figure 7). The Equinox Stone, Spring Stone and Cube are other three up-right stones.

Individual Stones of Stone Line II

There are 88 stones in Stone Line II. With rare exception these stones lie at the ground surface indicating they are like the stones in Stone Line I consistently 10 to 20 centimeters in thickness. The average length of the stones in Stone Line II is greater than the stones in Stone Line I giving the line a more massive appearance. There is only one up-right stone in Line II standing approximately 0.6 meters high. There are eight transverse stones and like those in Stone Line I the transverse stones vary in size and do not appear in any order or standard spacing distance along the line. Satellite stones also occur adjacent to the line and generally coincide with gaps in the line. However, very large gaps occur along the northeastern 15 meters of the line suggesting that the line was not completed or it was disturbed after construction. This conclusion is further supported by the occurrence of a pile of loose stones at the northern end of the line.

BELOW IS A MAP I MADE OF STONE LINE 1

The map of the line is in figures from my field notes. The map shows two things. The above view shows that the stones as you walk along-side the line. The figure below each stone is its relative height above the ground surface. The scale is on the right side of each figure but may be hard to understand. Below I describe stone #1 for comparison to other stones.

For comparison to other stones, stone #1 is at the extreme upper right of the first figure. On Tomales Point it is located at the extreme southern side of the ridge where landslides carry soil and rock down steep cliffs to the beach below. It is a flat slab 1.1 meter long and 0.8 meters wide. It does not rest very much above the ground, but my inspection suggests it is buried relatively deep. So, this is a very big stone.

Map Figure

Stone #1 Location

Celestial Features

A larger view of the Tomales Point study area shows all the mounds. Curiously they appear to be laid out to resemble the night sky near Polaris, the North Star. Each is marked by a star symbol. A comparison to star maps suggest that the mounds represent stars that make up the constellation we call Cassiopia. All the mounds except one seem to co-inside with celestial features in this part of the sky except one. The MIAMO team calls it the Sol mound. We are not saying that these monds were placed to mimic Cassipeia. But the mound distribution look like it mimics this part of the sky. Not surprising, this part of the sky is over Tomales Point every night of the year.

The freaky thing is that if you look at Cassiopeia as it would appear from our nearest neighbor Alpha Centari then the Sol mound fits quite well.

The whole pattern also seems to fit with the North star and how these stars appear to move around it. The red circle marks the track in the sky that Cassiopeia follows around Polaris. This track intersects some very important rock features at the site.

A NEW HYPOTHESIS FOR THE ORIGIN AND FUNCTION OF THE STONE LINES KNOWN AS THE SPIRIT OF JUMPING-OFF ROCKS, TOMALES POINT, MARIN COUNTY, CALIFORNIA

Stephen D. Janes M.A. Ph.D., California State Professional Geologist #4411, 230 Morrissey Blvd. Santa Cruz, California 95062

Crossing Tomales Point, two linear arrays of stones known to the Coastal Miwok as “Spirit Jumping-Off Rocks” have been reported by historians to be a wall or property line built sometime in the nineteenth-century. Until recently no detailed description of the stone lines has been available and no written documentation supporting the historic origin has been found. Ground surveys in the area have not found any artifacts such as ceramics or debitage, and archaeologists generally agree with the historic origin. In 2013 the first detailed descriptions of the lines were collected and a set of stone metrics assembled. From these data several features of the stone lines were identified that are not consistent with the historic origin model. Instead, key marker stones within the line identify various celestial events including equinoxes, solstices and star settings. Intervening stones may represent temporal sequences such as seasons or the timing of other key celestial events. The age of these structures remains unknown.

Cruzando el punto de Tomales, los historiadores han divulgado dos arsenales lineales de piedras conocidos al Miwok costero como “rocas que saltan del alcohol” para ser una línea de la pared o de la característica construida alguna vez en el siglo XIX. Hasta hace poco no se ha encontrado una descripción detallada de las líneas de piedra y no se ha encontrado documentación escrita que respalde el origen histórico. Las prospecciones de tierra en la zona no han encontrado ningún artefacto como la cerámica o el debitage, y los arqueólogos generalmente están de acuerdo con el origen histórico. En 2013 se recogieron las primeras descripciones detalladas de las líneas y se reunió un conjunto de métricas de piedra. A partir de estos datos se identificaron varias características de las líneas de piedra que no son consistentes con el modelo de origen histórico. En su lugar, los marcadores clave dentro de la línea identifican varios eventos celestes incluyendo equinoccios, solsticios y ajustes de estrellas. Las piedras que intervienen pueden representar secuencias temporales tales como las estaciones o el momento de otros eventos celestiales clave. La edad de estas estructuras sigue siendo desconocida.

Tomales Point is part of the larger Point Reyes National Seashore which is located along the Pacific coast 30 kilometers north of San Francisco and is defined by the elongate landmass directly west of Tomales Bay (Figure 1). Geologically the area is of particular significance because much of it is composed of granitic rocks which have been displaced by the San Andreas Fault hundreds of kilometers northward (Clark, Brabb, Greene, & Ross, 1984). The fault occurs directly beneath Tomales Bay. The geomorphology of the region therefore is influenced by its proximity to the San Andres Fault which has produced northwest trending narrow features including Tomales Bay and Tomales Point. Tomales Point is relatively narrow ridge approximately nine kilometers long that separates the bay from the Pacific Ocean and affords a panoramic view of the surrounding area.

The “Spirit Jumping-Off Rocks” is a poorly known line of stones located on the crest the Tomales Point peninsula. It is composed of two linear arrays of rectangular stones with compass bearings north 28 degrees east and north 35 degrees east respectively (Figures 2 and 3). The term “Spirit Jumping- Off Rocks” is derived from Coastal Miwok oral history (Gardner, 2007; Collier & Thalman, 1991). Known from the sixteenth-century the Coastal Miwok occupied Bodega Bay, the Point Reyes peninsula along Tomales Bay and areas to the east (Kroeber, 1976). Along the eastern shore of the Tomales Point peninsula six former Miwok sites have been identified located below the area where the stone lines occur (Edwards, 1970). However, the Miwok are not known to construct rock features (Dougan, 1998) and make no claim that they were the builders of the stone lines.

Because the stone lines appear so regular, historians and archaeologists have concluded that they were constructed to define a property boundary and at one time may have been part of a wall (DeRooy & Livingston, 2008; Livingstone, 1993). If the lines were once a wall, several thousand stones would have been required to construct a wall, but only a few hundred are now present. The missing stones are not located near the line and would have been removed from the area. Alternatively, the lines of stones were used to define a property boundary. An 1854 survey map shows a line in the approximate location where the stone lines occur, but refers to it as a fence (Wing, Lida and Wearing 2014). Other fences also are depicted on the map where no fences occur today. No written documents such as journals, diaries, newspaper articles, or property plot plans are available describing the wall or property line or its construction, and historians have acknowledged the possibility that the stone lines are older and may have been constructed by “paleo-indians” (Gardner, 2007).

The only detailed description of historical and circumstantial information leading to inferences about the origin and function of the lines has been produced by Wing, Lida, & Wearing (2015). In addition, Kate Lida and Emily Wearing produced a database of the stone metrics including length, width and height of each stone and other features like gaps and the number of stones adjacent to the line (Wing, Lida, & Wearing, 2014). From these data and limited historic information they made comparisons to other stone walls in the region. While the historic hypothesis is one explanation for the origin and function of the lines, the stone metrics data set reveals several features that do not suggest a wall or property line. Additional investigation and descriptions of the stones and other geomorphic features over a larger area provides more evidence to test the historic origin hypothesis and suggest other models.

Research Methods

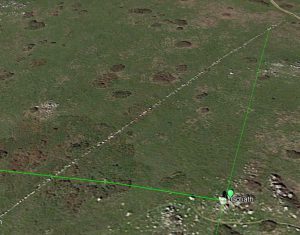

Initial analysis of the geography and geomorphology of the study area were assessed using satellite photography from Google Earth R (Figure 3). Ground surveys were conducted using a Brunton Pocket Compass adjusted for magnetic declination and the United States Geologic Survey 7.5-minute Tomales Quadrangle. Several geomorphic features were described in detail and examined to determine if they were natural bedrock outcrops. Soil thickness was determined by inserting a thin steel rod until it impacted buried bedrock.

As noted above a stone metrics database was constructed by Wing, Lida, & Wearing (2014 and 2015). Michael Wing supplied this author with an early draft of their paper and the original stone metrics database. A graphic representation of the stone metrics was created to use in the field as a map (Figures 4A, B and C). The map and database were checked in the field and used to further describe the line shape and orientation, the specific stone dimensions and shapes, and to identify unique features along the lines. Ground surveys were conducted in a primary study area of 50 acres and identified numerous stone alignments between features along the stone line and other stone features adjacent to the line. These alignments were measured with the compass and later checked using a tripod mounted transit.

Celestial data for comparison with ground surveyed features were obtained from the website, neave.com/planetarium. This is an interactive star map and virtual sky program depicting celestial objects and their transits across the sky at a selected latitude and longitude. The transit patterns of the sun, moon, planets and the ten brightest stars in the night sky over Tomales Point were identified for the period from 1500 A.D. to the present. These data were checked in the field and bearings of the transits and settings of the brightest stars were measured over several nights.

Results

There are two lines. Designated herein as “Stone Line I” and “Stone Line II” (Figure 2). Stone Line I, is a group of 241 stones 160 meters long and follows a compass bearing of north 28 degrees east across Tomales Point. The stones are numbered in this study from south to north with the first stone occurring near the western cliff edge of the peninsula. The end of Stone Line I is marked by stone #241 and is located near the crest of the peninsula ridge. Stone Line II begins ten meters north of the northeastern end of Stone Line I. It is composed of 75 stones arrayed over 88 meters and follows a compass bearing of north 35 degrees east. Historians suggest that the stones were assembled originally as a single line (DeRooy & Livingstone 2008). This requires the assumption that the two lines present today were once connected by a now absent line of stones approximately ten meters in length. There is no evidence of these “connecting” stones (e.g. partial line, scattered stones, geomorphic expression) present at the site. For this study, it is inferred that there originally were two stone lines.

Stone Line I

Most of the 241 stones of Line I typically lie at the ground surface surrounded by soil much like a series of stepping stones. Most of these stones are flat and in some cases partially covered by vegetation (Figure 5). Unlike stepping stones the line stones are quite thick and show signs of settlement into the underlying soil. The stones are typically 0.4 to 0.5 meters in width and have been arrayed in many places so that one edge of each stone is aligned to the next making the line appear very uniform. Though they may vary in length approximately 85 percent of the stones fit this description. The few exceptions to this typical shape and size include; tall and/or upright stones, large slabs wider than 0.5 meters, large transverse stones in which the long axis of the stones are set at a right angle to the trend of the line, and gap stones, isolated small stones at the center of relatively large gaps in the line.

Gaps between the stones are typically no more than 0.1 to 0.2 meters wide and in several cases the stones lie directly against one another. In a few places along the line larger gaps (0.3 to 0.5) occur and these gaps are typically associated with “satellite” stones. Satellite stones lie adjacent to the line, but are not part of the line. There is a close correlation between wider gaps and numerous satellite stones nearby, suggesting the satellites were once part of the line and have been displaced. There are two cases where several satellite stones occur along the line and are not adjacent to gaps. At these locations the satellites occur near tall stones and suggest that there may have been some additional structure to the line at these points. At two separate locations there are gaps each two meters in length. Near the center of each gap is a small stone (i.e. gap stone).

Stone Line II

There are 75 stones in Stone Line II. With one exception these stones lie at or near the ground surface. The average length of the stones in Stone Line II is greater than the stones in Stone Line I giving the line a more massive appearance. The only up-right stone in Line II is approximately 0.6 meters high. There are eight transverse stones in Line II. The transverse stones vary in size and do not appear in any order or standard spacing distance along the line. Satellite stones also occur adjacent to the line and generally coincide with small gaps in the line. However, very large gaps occur along the northeastern 15 meters of the line suggesting that the line was not completed or it was disturbed after construction. This inference is further supported by the occurrence of a pile of loose stones at the northern end of the line.

Geomorphic Features Near the Lines

Surrounding the lines are several isolated mounds of soil and loose boulders (Figure 2). Detailed inspection of these mounds indicates that they are not bedrock erosional remnants. Instead the mounds are composed of a core of soil and mantled with rocks to prevent the soil mound from washing away during heavy rains. An example of this are the “platform mounds” located 160 meters to the west of the stone lines (Figure 2 and 6). These mounds are stepped up the slope with soil cores and the steep west facing slopes are covered with a meter-thick layer of stones to prevent slumping. The tops of these mounds have been planed flat.

One mound is particularly significant because it occurs very close to Stone Line I and is capped by the single largest stone in the area (Figures 7 and 8). Referred to herein as the “Goliath Stone” this boulder is three meters high and approximately two meters in diameter. It has a flat bottom and sits on a semicircular ring of smaller stones. This orientation creates a small alcove beneath Goliath facing west toward Stone Line I. Because of its size and upright position, Goliath can be seen from great distances away from the ridge crest. There are several grooves on the western flank of Goliath (Figure 7). Only one of these grooves is caused by a fracture. The remaining grooves are shallow cuts in the rock face. Weathering patterns on stones in the study area do not suggest that these grooves were formed naturally and this may be a weather worn petroglyph. The petroglyph forms the shape of a six-rayed star.

Unusual Features Along the Stone Lines

While most stones making up Stone Line I are flat and narrow there are some exceptions. Stones exceeding 0.4 meters high and/or placed upright along the line are referred to herein as “tall” stones. There are eight tall stones in Line I and one in Line II (Figures 4 and 9; Table 1). Some of these tall stones show signs of displacement due to differential compaction of soils, animal burrows, frost wedging and other ground disturbing processes and may have been taller in the past. However, there are four tall stones in Line I that are clearly installed in an upright position and stand much higher than the adjacent stones (i.e. #38, #55, #69 and #226; Figure 4).

Stone #38 occurs 29 meters from the southern end of the line (Figures 4A and 5). Unlike the flat stones nearby it is placed upright and in a transverse position along the line. The area around this stone is also unusual because there are several satellite stones, suggesting this stone was part a more complex structure that has fallen away from the main line course. A compass bearing from Goliath to stone #38 is directly due west creating an alignment azimuth of 270 degrees (Figure 9). Stone #55 is a relatively large upright transverse stone (Figure 4A). The alignment of this stone to Goliath is 9 degrees north of west (i.e. azimuth 279). Stone #69 is a very large upright line parallel stone (Figure 4A). The alignment of this stone to Goliath is 21 degrees north of west (i.e. azimuth 291). Stone #226 occurs a few meters south of the northern terminus of Stone Line I (Figures 4C, 9 and 10). This is the tallest stone in Line I and is twice as high as any other stone. It is installed in an upright position and bounded to the north and south by massive though not tall stones (i.e.# 224 and #228). Stone #226 is located on the line in a north to south alignment with the Goliath Stone (i.e. azimuth 0).

In addition to the tall stones, there are 12 stones that are significantly larger than the typical stones in Line I (Table 1). These stones stand out from the line as massive blocks and often are buried relatively deep into the surrounding soil. The stones are estimated to weigh between 3000 and 4000 pounds each. Stone #25 is one of the largest stones in Stone Line I (Figure 4A) and is estimated to weigh 3500 pounds. Stone #81 is a relatively long, wide, and tall block. There are several satellite stones nearby and this stone marks the point where Stone Line I occurs closest to the Goliath Stone (i.e. 42 meters, Figure 8). The alignment of stone #81 and Goliath has a compass bearing of 31 degrees north of west (i.e. azimuth 301). This alignment marks the transit of the sun on June 21, the Summer Solstice. Viewed from Goliath the sun sets directly behind stone #81 on that date.

There are two gaps in Stone Line I that are approximately two meters long and where satellites were not found (Figures 4A and 4B). These gaps occur at 2 and 75 meters along the line respectively as measured from the southern end (Figure 9). At the center of Gap 1 is the relatively small stone #2 which has a unique shape (Figure 4A). This stone has triangular facets forming a pyramidal shape and a pointed crown. The stone is nearly completely buried, but the pointed crown can be seen above the ground surface. The alignment bearing between this stone and Goliath is 21 degrees southwest (i.e. azimuth 249). Gap 2 is two meters long and there are three small stones near the center. Of these #114 appears imbedded in the ground and is a small transverse stone. The other two stones appear out of place and might be considered satellite stones. The alignment bearing between stone #114 and Goliath is 55 degrees northwest (i.e. azimuth 325).

Because the upright stones #38 and #226 are placed at specific locations relative to Goliath to mark alignments of East-West and North-South respectively, it can be inferred that other stones might serve as markers. This is further suggested by the tall massive stone #81 which marks the Summer Solstice. To test this hypothesis, alignments were measured between Goliath and the two large gaps, the four tall/upright stones, and the eleven massive stones along the Stone Line I (Table 1). Also measured is the alignment between Goliath and the upright stone in Stone Line II. This data set was then compared to compass bearings of alignments between Goliath and the points where the ten brightest stars over Tomales Point set throughout the year (Table 2).

The correlation of star settings to unique stones along Stone Line I is significant (Table 2 and Figure 9). Only the stars Altair and Antares are not marked. The stone marker for Antares would have occurred several meters south of the present southern end of the line in an area lost to head ward erosion of the western cliffs by landslides. A Winter Solstice stone marker would also be south of the cliff edge. It is possible these markers were once present if the line extended some distance further to the south. Altair is the seventh brightest start in the night sky. It sets in close proximity to the setting markers for Betelgeuse and Procyon. The marker may be stone #61, but this is not a unique stone feature.

Four massive blocks do not appear to coincide with star settings, solstices or equinoxes. For stone #181 this is striking because along the alignment of #181 with Goliath there are seven other stones extending the alignment 100 meters northwest of Stone Line I (Figure 9). The alignment bearing is also unique because it is matched to the northeast by the alignment between Goliath and the only upright stone in Line II (Figure 9). These two alignments form a 30 degree angle bisected by the north to south alignment. Within this angle the constellation presently known as Cassiopeia dominates the night sky and descends to its lowest point between these alignments without setting as it circles Polaris.

Discussion

As there are many old stone walls crossing the hills east of Tomales Bay, it seems reasonable that historians might conclude that the stone lines crossing Tomales Point are the remains of another wall built by ranchers in the nineteenth century. However, no written historical documents have been found to confirm this conclusion. In part, because archaeological surveys have not found any cultural artifacts like shell middens, pottery sherds or debitage near the lines that might suggest an earlier origin or different function, the historical origin hypothesis is generally accepted.

However, the lines are not alone. There are several soil and rock mounds scattered along the crest of Tomales Point near the lines. Some of these mounds may be natural erosional remnants, but some clearly are not. Rock outcrops on grass covered slopes in the area are typically exposed by down slope creep of the soil and appear as relatively flat features free of debris, because loose material continuously makes its way down the slope to drainage bottoms. In contrast, mounds on the slopes near the stone lines seem to have been built up and resist natural erosional processes. This is particularly clear for the two platform mounds (Figure 6) at the site which are composed of a soil core and steep west facing slopes that are mantled by rock to prevent erosion. In addition, something or someone has planed off the tops of these mounds. These flat surfaces provide an excellent platform for viewing miles of the coastline.

Careful examination of the mound where Goliath stands suggests that it was also modified by placing the massive stone on a semicircular ring of smaller stones which sit of a thin layer of soil. This stratigraphy suggests that at least this part of the mound is artificial. The proximity of Goliath to Stone Line I further supports this inference.

A formal description of the stone lines has not been available until recently (Wing, Lida and Wearing 2014). The description includes size metrics of the individual stones and offers some evidence that the stone lines were never walls. While most of the stones are relatively small and flat, there are 12 massive stones that are located at irregular intervals along the lines. These larger stones are estimated to weigh several thousand pounds and seem unnecessarily large for a stone wall. In addition, only four stones were clearly placed in an upright position rather than laid flat. And, there are two large gaps in Stone Line I and one large gap between the lines that cannot be readily explained.

The striking coincidence that stone #226, the tallest stone in Line I, forms a north to south alignment with Goliath located directly adjacent to the line suggests that other alignments with Goliath might be present. This is confirmed for upright stone #38 which is directly west of Goliath and marks the sunset on the equinoxes. It is also confirmed for massive stone #81 which is located along an alignment coincident with sunset on the Summer Solstice. In each case these stones are among the small subset of stones that are upright and/or unusually large. Such alignments suggest that the stone lines might serve in part as markers of various celestial events.

With hundreds of stones in the lines any alignment can be constructed. A test must eliminate most of these stones to be of value. To test the celestial marker hypothesis only alignments between Goliath and 16 unusual stones (e.g. massive, upright, and/or tall) and the two gaps in Line I were measured. These alignments were compared to the alignment of Goliath with the point of star setting for the ten brightest stars in the night sky over Tomales Point. This comparison showed a high correlation for the unique stones with star settings.

A careful examination of Goliath indicates it serves as a “index” point articulated to Stone Line I and II serving as a critical observation point. It is located at a point on the peninsula from which an observer can view a 180-degree arc of the horizon in which all ten bright stars and the sunset on the solstices and equinoxes can be seen. The presence of a large petroglyph of a star on the western flank of Goliath further suggests this hypothesis.

Stars in apparent proximity to each other in the night sky but not visible in daylight can be grouped by season. Sirius, Procyon, Rigel and Betelgeuse are visible in the Winter. Arcturus and Antares are visible in the Summer. Vega and Altair are visible in the late Summer and Fall. These seasonal events along with the solstices and equinoxes suggest the stone lines may function as a calendar. There are at least 25 species of marine life in the Tomales Bay and adjacent Pacific waters that can serve a food sources for human consumption. Tracking their seasonal productivity might be one function of such a calendar. As an example, most shellfish are toxic in the summer months due to the presence of microorganisms in the marine environment. As a source of food it would be critical to avoid them at that time.

The possibility that some alignments with Goliath might be coincidental cannot be ruled out. While the present database serves as a test of the “celestial calendar” hypothesis, more study is needed. Lunar and planetary transits of the night sky are yet to be examined. Additionally, the age of the lines is not known and having this information would help address who might have constructed the lines. Because there is a name for these lines in the oral history of the Coastal Miwok, suggests that they were constructed several centuries before European arrived in the area.

Closer examination of the mounds associated with the stone lines and some excavation might be required. Additional, archaeological surveys is also recommended. However, Tomales Point is an animal refuge within the larger Point Reyes National Seashore and excavations would cause significant disturbance of the animal populations. Continued detailed descriptions of the lines and surrounding geomorphology by simple observation may be the only investigative tool available for some time.

Acknowledgements

I was first informed about the stone lines by Renee Buchanan who participated in an archaeological field survey of Tomales Point. As noted above, the detailed measurements collected by Kate Lida and Emily Wearing continue to be a valuable source of data describing the stone lines. I am also grateful to Professor Michael Wing for supplying me with an early draft of their paper and the stone measurement data set. Field observations were also provided by Michael Cloud during various visits to the study area. Mark Hylkema, California State Archaeologist has been an advisor on various archaeological issues throughout this project.

References Cited

Joseph Clark, Earl Brabb, Gary Greene and Donald Ross

1984 Geology of Point Reyes Peninsula and implications for San Gregorio Fault History In Tectonics and Sedimentation Along the California Margin: Crouch, J.K. and Bachman, S.B. eds., Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists, Pacific Section, Book 38, p. 67-86.

Carola DeRooy and Dewey Livingston

2008 Images of America, Point Reyes Peninsula: Olema, Point Reyes Station, and Inverness, Arcadia Publishing, Charleston, South Carolina, 2008.

Michael Dougan

1998 Myth, mystery, history – all in one, San Francisco Examiner, San Francisco, California, October 4, 1998.

Robert Edwards

1970 A Settlement Pattern Hypothesis for the Coast Miwok Based on an Archaeological Survey of Point Reyes National Seashore, in Contributions to the Archaeology of Point Reyes National Seashore: A compendium in Honor of Adam Treganza, Treganza Museum Papers Number Six, R.E. Schenk Editor.

Gavin Gardner

2007 A Cultural Resources Study of the Spirit Jumping Off Rocks Site, Point Reyes National Seashore California, Rohnert Park, California, Anthropological Studies Center, Sonoma State University.

Alfred Kroeber

1976 Handbook of the Indians of California, Dover Publications, Inc. New York.

Dewey Livingston

1993 Ranching on the Point Reyes Peninsula: A History of the Dairy and Beef Ranches within Point Reyes National Seashore, 1834-1992. Point Reyes Station, California, Point Reyes National Seashore.

Michael Wing, Kate Lida and Emily Wearing

2014 The stone alignment on Tomales Point, Point Reyes National Seashore: Evidence for a historic-period origin. Alta, California, Unpublished manuscript.

2015 Stone-by-Stone Metrics at Point Reyes National Seashore, Marine County, Alta, California, California Archaeology, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 245-264.